Recovery under way in Mena countries but dangers loom, IMF says

The economic recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic across the Mena region is uneven and low-income states must press on with reforms and job creation or risk social unrest, according to the International Monetary Fund.

After contracting 3.2 per cent in 2020, the Mena region is forecast to grow about 4.1 per cent this year and in 2022, upward revisions of 0.1 percentage points and 0.4 percentage points since April, the fund said.

In large part, the upgrade is a reflection of the improved performance of stronger economies in the region.

“What I can tell you is [that] 2021 is the year of recovery. Economies are doing well since the beginning of the year. We see an improvement in the outlook,” Jihad Azour, the head of the IMF's Middle East and Central Asia department, told The National.

However, the “recovery is not even” and not all countries have the same economic conditions, with those that rapidly vaccinated their populations and introduced measures to protect their economies quickly, faring better and rebounding faster, he said.

While the region made transformative changes with the uptake in technology and increased digitisation, not all countries are on par.

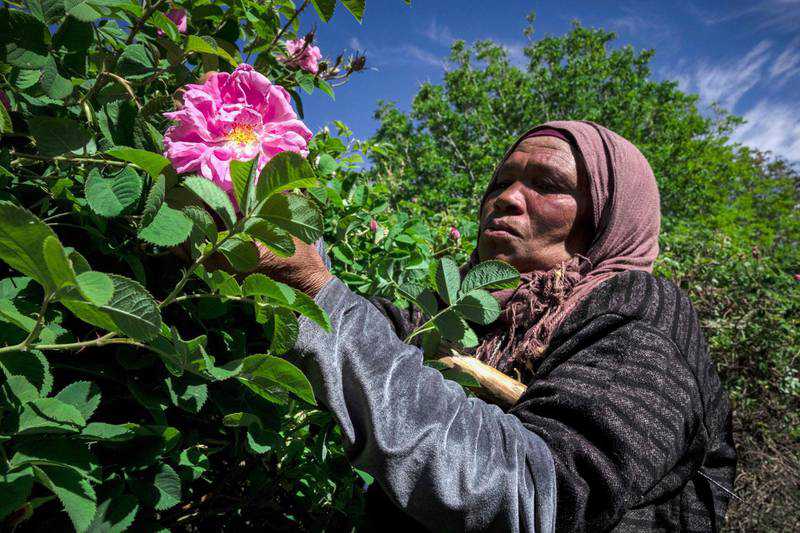

Although certain countries such as Morocco introduced economic reforms and are integrated into the global supply chain, which helped them rebound, other low-income countries are lagging and vulnerable.

Rising inflation and surging energy costs that have led to food prices surging 40 per cent this year present risks that are more pronounced for poor countries and exacerbate the effects of the pandemic on fragile states.

The pandemic sharply affected countries that had a limited capacity to vaccinate, with vulnerable groups in society such as women, youths, those in the informal sector and small and medium enterprises affected the most. The average unemployment rate for the Mena region rose to 11.6 per cent last year.

Inflation in the Mena region is forecast to hit 12.9 per cent this year, up from 10.5 per cent in 2020, before falling to about 8.8 per cent in 2022, according to the fund's estimates. It has been forecast at about 195 per cent and 39 per cent this year in Sudan and Iran, respectively.

“When we look at … mostly oil-importing countries, we see a certain number of challenges: low growth, low productivity, high debt, high inequalities and high unemployment,” Mr Azour said.

“When you have low growth and high debt, it increases vulnerabilities. If inflation is to persist, you need to address it and this may require adjusting interest rates," he said.

"If we see a change in the global financial markets, which means that maybe interest rates could go up globally or access to international capital markets will be less accommodative than it is now, this could have an impact.”

While the region's oil exporters will benefit from the recovery in global demand, higher oil prices, and wider vaccine coverage, oil-importing countries are expected to register an increase in gross government debt (projected at more than 100 per cent of GDP in 2021).

That has led to an increase of about 50 per cent in gross financing needs for 2021-2022 ($390 billion) compared to the 2018-2019 period, according to the IMF.

“The risks we are seeing today that need to be addressed [are] high debt, scarring effect, impact on labour and the need to prepare for a large transformation through additional investment, and some of those countries do not have enough resources for that,” Mr Azour said.

“It is not the time to relax. We need not to underestimate the impact of this crisis on SMEs and you need to move fast in rehabilitating labour.”

Unemployment increased by 1.5 per cent to 2 per cent this year across the Mena region while youth unemployment was between 25 per cent and 27 per cent, said Mr Azour.

Countries that do not have the fiscal space need to assume a multipronged approach as they look to get back on track, he said.

They need to come a full circle in addressing Covid-19 and hasten their vaccination campaigns. In tandem, governments need to recalibrate measures that were introduced during the crisis and focus on those in need as they also pursue structural reforms, Mr Azour said.

“If you want to increase productivity, if you want to create jobs, you still have way to go by reforming the public sector, recalibrating the role of SOEs [state-owned enterprises] and give more space to the private sector,” he said.

Last month, Egypt's Public Enterprise Minister Hisham Tawfik said the country was putting an end to loss-making SOEs and turning to the private sector to fuel the country's economic recovery. In 2018, Egypt identified 23 SOEs that could either be listed on the Egyptian stock exchange or potentially sell additional stakes. However, the pandemic contributed to delays.

“The real name of the game today is to finish the work on turning a page on Covid; you need to address the stabilisation issue but you need to do it in an inclusive way," said Mr Azour.

"What this crisis showed us is that the informal sector is not as good [at] buffering a crisis as it used to in the past, so when it comes to social assistance, you need to be more targeted to help people get additional skills and redirect your spending to providing more social support and investing in technology and 5G."

Aside from countries focusing on health, education and the expansion of social safety nets, they need to leverage digital technology that was instrumental during the pandemic while also adjusting their policies in line with climate change needs, the fund said.

The IMF is cognisant of possible social unrest across the Mena region.

“We [see] vulnerabilities coming and this is why we are highlighting the importance of addressing those inclusion issues," Mr Azour said.

"If you do not provide additional space for job creation, you will have and you will keep having challenges to social stability in the region.”

Tags :

Previous Story

- ‘Domestic production of industrial machinery needed’

- Bangladesh an emerging big monetary force, says Iranian...

- Tension in Middle East: May deal blow to...

- Oil tops $70 as Iran, Trump exchange dangers

- Iran discovers new oil field with over 50...

- Iran, Bangladesh to Launch Direct Flight Soon: Envoy

- Build unified sustainable blue economic belt: PM

- Emirates to launch 46 additional flights to Saudi...